If you are visiting the United Arab Emirates, you will surely encounter the majestic beauty of Arabic calligraphy. From mosque facades to the interiors of the most luxurious shopping centers, from traditional restaurant signs to contemporary art installations decorating the city, the elegant characters of Arabic script are everywhere. In historic souks as well as in the ultramodern skyscrapers of Downtown Dubai, this millennia-old art continues to define the city’s visual identity, creating a fascinating bridge between Emirati cultural heritage and cosmopolitan modernity.

But what does this art form truly represent? Arabic calligraphy is one of the oldest and most respected art forms in the Islamic and Arab world, characterized by the aesthetic use of writing based on the Arabic alphabet. This writing system is one of the most widespread in the world: the Arabic alphabet, with its 28 letters and right-to-left writing direction, is considered the second most widely used alphabetic system globally after the Latin alphabet in terms of number of speakers and diffusion beyond its original linguistic boundaries.

Origin and Meaning of Khatt

In Arabic, calligraphy is commonly called khatt (خَطّ), a term derived from words meaning “line,” “design,” or “construction,” emphasizing the graphic and compositional nature of this practice.

Arabic calligraphy did not originate simply as text decoration, but as an autonomous art form that has accompanied the cultural and religious history of Islam.

Calligraphy and Culture

Arabic calligraphy is deeply intertwined with Islamic culture: it is not only a tool for transmitting the sacred word, but is also seen as a way to manifest beauty, spirituality, and aesthetic discipline. Due to the symbolic value of the written word, calligraphic writing was historically valued more than other figurative art forms in Islamic societies.

Calligraphers were revered for their ability to unite art and devotion, and the practice required years of discipline and study to achieve mastery.

Main Calligraphic Styles

With the development of khatt, numerous calligraphic styles emerged, each with its own aesthetic characteristics, functions, and rules:

Kufic: one of the oldest styles, born in the city of Kufa in Iraq, is known for its angular and geometric forms. It was widely used for monumental inscriptions and for early copies of the Quran, dominating the calligraphic scene until the 10th century.

Naskh: standardized and codified in the 10th century by the celebrated calligrapher and vizier Ibn Muqla (885-940), is characterized by more rounded and legible forms. This cursive style, already existing from the first century of the Islamic era, gradually replaced Kufic as the primary script for Quranic manuscripts and is still widespread in printing and daily writing thanks to its excellent legibility.

Thuluth: elegant and monumental, with elongated letters and harmonious lines, was invented by Ibn Muqla during the Islamic Golden Age. It has been used historically for architectural decorations, titles of sacred works, and inscriptions on mosques, and is considered one of the most majestic styles of Arabic calligraphy.

Diwani: an ornamental and complex style developed during the Ottoman Empire (16th-early 17th century), famous for its intricate interconnection of letters and its use in official documents of the Ottoman court. Its decorative character makes it particularly appreciated for certificates and works of art.

These are just a few examples: there are dozens of variants and sub-styles that testify to the extraordinary expressive richness of khatt, including Muhaqqaq, Rayhani, Tawqi, and Riqa, each with distinctive characteristics and specific areas of use.

The Revolutionary Contribution of Ibn Muqla

Abu Ali Muhammad ibn Muqla, who lived in Baghdad during the Islamic Golden Age, was not only an important vizier of the Abbasid Caliphate but also the father of classical Islamic calligraphy. His fundamental innovation was the introduction of a geometric proportional system for calligraphic writing, based on precise mathematical principles.

Ibn Muqla defined the proportions of letters in relation to three key elements: the dot (nuqta), the height of the letter alif, and a circle whose diameter equals the height of the alif. This system, called al-khatt al-mansub (“proportioned script”), transformed calligraphy from an intuitive practice into a codified art, allowing subsequent calligraphers to learn and perfect styles in a systematic way.

Technique and Tools

Traditional calligraphers use the qalam, a reed or bamboo pen cut obliquely in a specific way to control the thickness and angle of lines. The preparation of the qalam is an art in itself: the cutting of the tip must be precise to obtain the characteristic strokes of each style.

In addition to the qalam, calligraphers use quality inks, traditionally prepared with soot, gum arabic, and water, and special paper or parchment. Mastering these tools requires years of practice under the guidance of a master, as each stroke is significant both for its linguistic meaning and visual impact. Traditional learning occurs through repeated copying of classical models (mashq) until technical perfection is achieved.

Arabic Calligraphy in Dubai: Tradition and Innovation

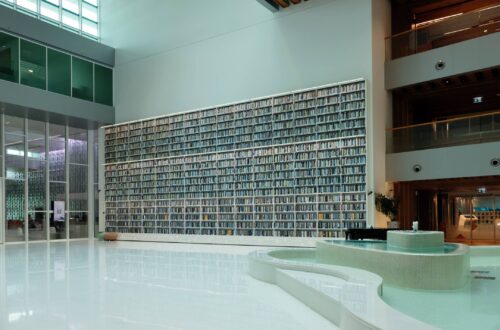

In Dubai, Arabic calligraphy is experiencing an extraordinary renaissance. The city hosts numerous contemporary calligraphy artists who reinterpret this millennia-old tradition in a modern key. Walking through Alserkal Avenue, the art district of Al Quoz, or visiting galleries such as Tashkeel and The Jamjar, one can admire works that blend classical calligraphy with contemporary techniques.

Even in public spaces, Dubai celebrates this art: the Museum of the Future incorporates Arabic calligraphy into its iconic facade, transforming poetic verses into architecture, and numerous mosques in the city, from the historic Jumeirah Grand Mosque to the monumental Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque in Abu Dhabi, present spectacular examples of traditional calligraphy that leave residents and visitors breathless.

This article is intended for informational and cultural purposes only. While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, if you notice any inaccuracies or have suggestions, please contact us at hello@staging11.ibsg.space